If you have been reading this blog for the past couple months since I started it back up, you may have read the series of 3 posts that I did on the recent Merzbow album “Takahe Collage” (1 2 3). Those posts were a bit more analytical than they were philosophical in nature, but the two do tend to go hand in hand to a certain extent.“My God! What has sound got to do with music!” – Charles Ives

I’ve had some time to put together some more thoughts on the topic of music as abstraction, noise as music and how it relates to the thoughts and motivation of other artists of all types within that realm. I wrote this short paper for a presentation in a seminar on the history of 20th century music. I offer it below:

October 9, 2013

The main thing that I would like to discuss today, and I want to get a dialogue going on this, is the idea of what a group of musicians considers to be music and what they consider “noise.”

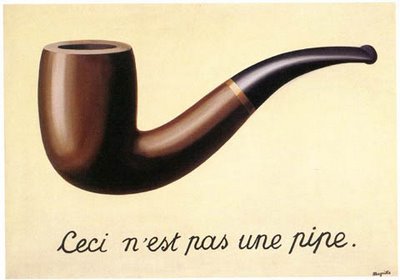

We’ve been looking at how the art world relates to the musical world, showing how the Rite of Spring’s choreography relates to cubism, and primitivism. We’ve talked about modernism and post-modernim, and I’d like to talk a little bit about abstract art, dadaism, music and noise.

First, I want to give you an idea of what I’m talking about with a painting by Jackson Pollack. We’ve probably all seen his paintings, and they have given way to many discussions of whether they are or are not art. Is something art just because the artist says it is? Or can anything be art? How about a painting or sculpture by a Dada artist that takes random materials found on the street and fastens them together with purposely no organization? Does that lack of organization become the organization? Or are we, like Taruskin says, finding organization where there isn’t any simply because we are looking for it? Is music music just because the composer says it is, or can any and all sound be music?

There are plenty of electronic sound collage pieces that are made from “found sound” that has been manipulated. Is that manipulation what takes something from just sound to actually being an artistic statement? And think back to the first time that you heard Schoenberg or Webern or John Cage, or put yourself in the shoes of someone that only listens to top 40 pop music hearing Webern’s Op. 20 for the first time. What do you think that person would have to say about that music? Would they say that it was just noise? Could noise be just a word that we use when we don’t understand something?

Let’s listen quickly to a few short examples:

Frank Martin: Quatre pièces brèves: III. Plainte

Both guitars, right? But what does the timbre of Julian Bream’s guitar have to do with that of The Telescopes? They are both the same instrument, but the sound of guitar as we know it is an abstraction of what a guitar “really” sounds like. The sound of the guitar, when used in rock music, is merely a symbol. It doesn’t sound anything like a guitar. Instead the sound that is produced stands in for the sound of the guitar. It essentially is a wall of distortion. But, we have learned to accept that particular sound over time as being “a guitar.” Imagine if you were to play that Telescopes song for Andres Segovia, or Beethoven, or Bach. They would have NO IDEA what that sound was. We recognize it as such because we can picture in our head where the sound is coming from. We understand where it is coming from and we accept it. We understand so well that we don’t even think about it anymore.

Do we consider the sound of a distorted guitar from rock music to be noise? Or just noisier than what a “guitar” “should” sound like? And what should anything sound like?

What if we got even more abstract? Now onto Merzbow.“Is not beauty in music too often confused with something which lets the ears lie back in an easy-chair?” – Charles Ives

Merzbow is Japanese musician and writer Masami Akita. Since 1979 he’s released over 350 recordings, 6 so far this year. Included in that output is the amazing 50 CD Merzbox. This is the track “Tendeko” from the 2nd album he released this year, “Takahe Collage.”

Can we accept this as music? I would say that this is basically, to me, just another degree of abstraction. Merzbow is manipulating the sounds that he is generating, there are different timbres involved, different ideas that are brought in and then go out through the course of the piece. However, is this closer in timbre to “pure noise” for you?

And what exactly is a good definition of noise? Does it have to do with sound? There’s a book by Paul Hegarty called “Noise/Music: A History” that discusses “noise” in all of its contexts. Noise as basically any confrontation against our expectations. It could be in the form of a reaction to norms, or noise as antagonism such as with the band Throbbing Gristle, taunting and angering their audience purposely. Noise as anything added to the music or that distracts one from the music. But what happens when the noise is the music? And we still haven’t solved the problem of what is and is not considered music. If this “noise,” in whatever form that it may be coming in, is part of the performance (and is it really possible to get rid of all noise? Hello, John Cage) then is it really noise at all?

I think of it this way: John Cage’s music is the sound of philosophy. It gives us something that is challenging, it gives us something that questions what it is that we believe about something that we thought that we had such a firm grasp on. This music is something that gets us thinking and it is something that is provocative and it is daring and controversial, but it is also an outlet for something for someone that wants to create something.

Isn’t music itself an abstraction of our words and our voices? And, if so, noise music is still music in just the same way. I think that as we evolve we continually create further abstractions from where we started off, and eventually everyone catches up to that abstraction, and the definition of “noise” changes. Everything is a symbol for something else in music. Just think to the programmatic music of Strauss or Berlioz. Everything is symbol and everything is abstraction.