Glenn Branca’s 6th Symphony “Devil Choirs at the Gates of Heaven” has been my go-to large scale work lately. It brings to mind several thoughts that I have about music in general and about a composer’s intentions.

As I listen to a symphony by Branca (and I think that I have listened to most of them, and of the ones that I have listened to I have done so several times) I often find myself wondering what the score looks like. Immediately after trying to imagine the score I ask myself if that even matters. The next thing that comes to mind, especially when listening to this work in particular is how a composer (it can be any composer) can manage to have such a firm hold on their style, where their music is instantly recognizable, like Stravinsky or Webern or Ravel, yet still manages to say different things.

I guess that might be an assumption, that the composer has to be saying different things with each work that is produced. For example, listening to each of Branca’s symphonies, each (for the most part, No. 9 is an anomaly) calls for an army of guitars, and a drummer. There might be some other instruments mixed in there, but the most noticeable thing (and I think that it’s the thing that everyone that has every listened to Branca’s music, or at least knows about his music) are the guitars.

The cloud of noise that is created throughout the 6th symphony accomplishes different goals in each of the movements, yet it still (on the surface) remains just that – a cloud of noise. Of course, we can get into the argument about what noise is or what is considered noise, for days. For my purposes I’m going to say that noise in Branca’s symphonies is that cloud of sound. It’s so pitch saturated that it becomes pitchless and there are so many performers on stage, each of whom are attacking their instruments in a wild tremolo, that the intense, dense layers of rhythm become rhythmless. The music is recursive, and in being so creates a situation where everything that is becomes nothing, and everything that seems like nothing on the surface is what the piece is all about.

This might sound a little too vague, or faux-philosophical and lofty, but allow me explain. Let’s go back to how the cloud of noise is used in a couple of the different movements. Take the opening of the symphony: it starts quiet enough, but as the movement begins to take off the strummed guitars’ monotony severs itself into two different layers where one layer forms a consistent harmonic backdrop while the other layer allies itself with the percussion, providing sharp stabs of accent every so often. That “every so often” becomes more and more often as the movement progresses, yet the layer of harmonic noise continues underneath. It is steady and omnipresent. The growth of the movement occurs via the interplay of these two layers. So we could say that the cloud of noise, as it pertains to this movement, provides the backdrop. It is the base of sound, the music has no choice but to grow continually louder. By the end of the movement the layers come together again, combining their pitch and rhythm material into a dense haze.

As with all minimalist music the more that the piece repeats the material the more that the listener is allowed to search “inside” the sounds that they are hearing. Lines start to peak out from the cloud, some interplay comes into focus.

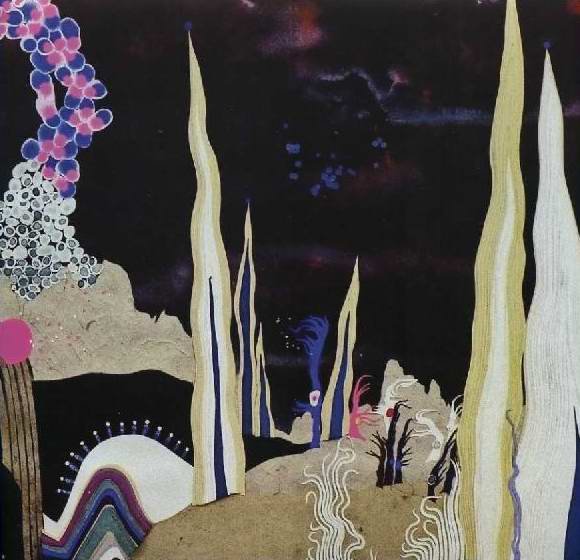

In the second movement an infinitely ascending line continues for the first four and a half minutes. The pitch material exists on its own, and there is no evidence of any guitar strings being attacked, or any strumming of any kind going on. All there is is pitch, and at the same time there really is no pitch. As soon as you are able to put your finger on it it is gone. There are some tones buried within that remain constant, while the upper limit continues to expand. It is music that describes infinity in many ways. Infinite space, infinite time (timelessness). Listening to this ever ascending line that seems like it is never going to reach its destination, it simply floats there, hanging in space. But there is motion, there is motion without direction. Sure it is ascending infinitely, but we have no idea as to the ultimate destination of that ascending line. The listener is left with no frame of reference, and that is exciting. There is a tension that is built up throughout the movement that is the result of all of this uncertainty. We begin to start listening for something specific to happen, we want there to be a great big arrival point. The longer that this ascent continues the more that we want to hear it and the greater our expectations become of something increasingly spectacular. It’s the same experience of needing to have a leading tone resolved, only this leading tone goes on for almost 5 minutes. When it settles down, and we decide that we have indeed reached a point of arrival there is an immediate release of all the tension that has been building up.

Symphony No. 6: Second Movement

I feel that this is something that more traditional composers aren’t able to harness. That tension. The ever growing intensity. Branca is able to create such a high degree of it here without any change in dynamic (it remains fairly loud consistently throughout the movement) and once again there are several other things that he is doing “without.” There still isn’t a clear statement of pitch. Instead we are presented with all of the pitches at once. That mass of pitch becomes, once again, cloudy and formless. The shape, however, changes and moves through time. The movement is more about an idea and a depiction than it is about pitch relations. It’s the development of one idea that fits into the work.

The third movement uses more monotony than anything else. Consistent chords ringing out with a steady pulse. Everything sounds like a downbeat. Again, as with minimalism, we have rhythm that is so persistent that it becomes anything but a rhythm. Our ear treats all the repetition as if it is something that can be ignored. This movement is also maybe the most abrasive of the symphony, and the most exciting, in my opinion. The final cadence brings us to the loudest caterwaul of sound that we have so far experience.

There is some dizzying contrapuntal work during the opening of the fourth movement, and finally we have some shifting layers of sound, where there was pretty much none in the first 3 movements. Two different lines bounce back and forth, a constant blanket of activity over which haunting and thin ephemera passing in and out of each channel in turn.

Symphony No. 6: Fourth Movement

That there can be such contradictions in a single work is interesting enough to think about. That they can be achieved in exactly the opposite way that one would first think is another thing altogether. Creating a work with no discernible use of pitch, by using all pitches all the time; and a work with formless rhythm while having a persistent rhythm throughout. As I’ve said a million times before, it’s about learning to hear differently, it’s about making sense of the apparent contradictions that are presented to us in a piece of music, the things that we never thought were possible, ideas that can not be expressed in any other way. Listening to music, such as a symphony by Glenn Branca, requires the listener to consider something that they have not only never considered before, but never thought about considering before.